And all the wounds became bridges: three faces of migrant identity in Mexico’s electronic music scene’

In conversation with Deeplinkin, Rizu X & Siete Catorce

Brutal as it may seem,

No scar is devoid of beauty.

Inside it’s a fine story is told,

Some pain perhaps. But also the story of its ending.

Scars are the stitches to memory,

An imperfect final touch that heals us

Through damage. The mark

That time imprints to make sure

that we don’t ever forget our wounds.

— Scars, Piedad Bonnett

I was born between epochs & cultures

born from an infected wound

a howling wound

a flaming wound

— Border Brujo, Guillermo Gómez Peña

October 27, 2020

TEXT Renata Iberia

Out of all the ruptures we may experience during our lifetime, there is one that transfixes our history and has the power to resignify us forever: departing from home. More than just a simple relocation, emigrating is a unique and irreversible break. The contained, hermetic body suddenly finds itself vulnerable, split in two, exposed. Unraveling the meaning of this dual condition (being here but also there or not being from anywhere) can be a complex and oftentimes confronting exercise. To trace the cartography of dislocation implies digging one’s hands into the chest and opening up remembrance, also looking into our past and realizing that we are made of words and stories, faces and landscapes, pain as well as joy. Not only that, this journey also leads us to historical memory and the eternal question of a collective identity.

For Mexican people going through this process in the United States duality has as many connotations as silences. One of the voices that recognized the urgency to reflect on this topic was that of Gloria Anzaldúa, Chicana poet, researcher and activist. In her 1987 book Borderlands / La Frontera: The New Mestiza (perhaps one of the most revolutionary works on border identity studies), Anzaldúa crystallizes the relationship between the two countries in a provoking, corporeal metaphor: the U.S.-Mexican border is a “1,950 mile-long open wound (…) where the Third World grates against the first and bleeds” (2,3). This wound is not only collective but also internal and solitary, “a struggle of flesh, … an inner war” (78) in which contradictory feelings coexist while blood flows and stains the world around it. However, at some point the wound just has to stop bleeding. The only thing that will remind us that it ever existed is a scar and, according to Anzaldúa, this is the exact moment when we can decide — almost in a heroic act — if we have the courage to name our wounds and transform them into human bonds, to turn our scars into bridges. From isolation to community, from blood to new life.

I spoke to three Mexican producers/DJs that have lived or live within the U.S. to understand how this metaphor operates in their memory and day-to-day life. In each conversation is a personal description of the wound-bridge process and its stages: the first clash, pain, and confusion that emerges after relocating and becoming aware of a hybrid identity, healing, resistance and creation. Another concept by Anzaldúa that will be useful will be that of Nepantla, a Nahuatl word that translates to“ space in-between” or “space in the middle” in which rebirths and reconfigurations happen, and also “forbidden knowledge, new perspectives on reality and alternate ways of thinking” (Interviews 5).

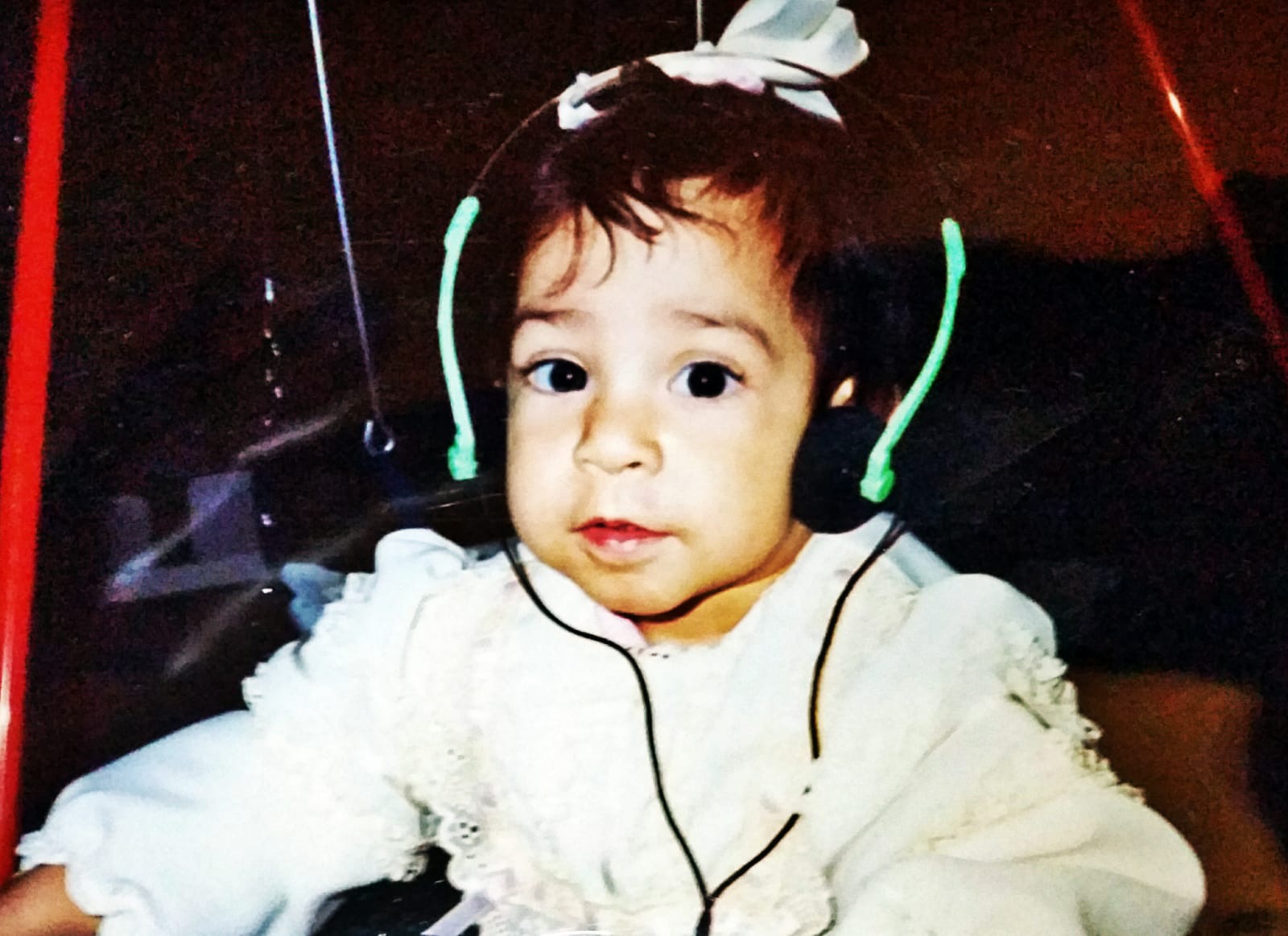

Nepantla is a fertile space for creation, inside it the wounds that divide our being start to heal. Each person in this compilation has inhabited Nepantla in their own way and they have reached a common creative point: electronic music. Each of them has emerged of this liminal space stronger and with a creative proposal in their hands. Nonetheless, what stands out the most to me is the fact that they have all found a way to work towards community through their music. For all that I have already mentioned, I want to express my gratitude for the trust that these people have vested in me. Thank you, Marco, Pil and Lizett, known in the electronic music world as Siete Catorce, Deeplinkin and Rizu X.

Within a few years of being born in Mexicali, Baja California, Marco crossed the U.S. border holding his family’s hand into their new home. The promise of a better future was in Oakland, California. Consequence of this early rupture with his hometown, Marco did not get to find out about his mexican identity until later in life. With an undoubtedly norteño accent, he tells me: “I didn’t realize I was Mexican. The only things I knew about Mexico were what my parents told me and what I knew about mexican popular culture”. An unknown territory and origin lived within Marco, only he did not know it. During his teenage years, however, a twist came: Marco and his family were forced to go back to Mexicali after his mom had a problem with her documents. Here is where Marco identifies the wound of his hybrid self: “When I had to go back to Mexico I didn’t give a fuck. I was about twelve and I didn’t think much about it. But when I grew up and was able to understand it, I realized that it did hit me. I lost all my friends, I changed a lot, I had to speak in Spanish and I realized I didn’t even know how to read it so well. It was very immediate, there was no time to think. Life was just feeling, living… Surviving.”

Out of this experience is that Marco gave life to Siete Catorce, a refined and at times even malicious inquiry into the limits of tribal, cumbia, dembow, pre-hispanic sounds, dubstep, techno and broken beat. After that confusing and contradicting rupture, Marco has found a brand new openness in the public’s ear. In his own words, “nowadays being Mexican is accepted and even enjoyed. It’s young people who are doing this kind of thing and agreeing on a rejection of the colonial… That shift is cool. I don’t know if I’m able to understand it, I just live it and I think it has to do with being receptive to new Mexican or Latin American music.”

When Marco mentions the rejection of the colonial I think back of Walter Mignolo, Argentinian researcher of decolonial thought, and his concept of de-linking. Briefly, Mignolo states how urgent it is to put our attention in all that colonizing hegemony has tried to erase (in this case we are talking about our musical culture) and then try to devise “other principles of knowledge and understanding” (Delinking 453), similar to Anzaldúa’s Nepantla. Marco is not just reproducing our country’s music and its structure. Instead, he is proposing a totally new approach, a rethinking through a de-linking: Siete Catorce gives new meanings to the music we already know and invites us to rejoice in its hidden possibilities. Marco is living proof that fragmentation and liminality can metamorphose into creativity: in the case of Siete Catorce, the result is a kaleidoscope of Mexican sound in which Marco’s hybrid identity gleams with pride.

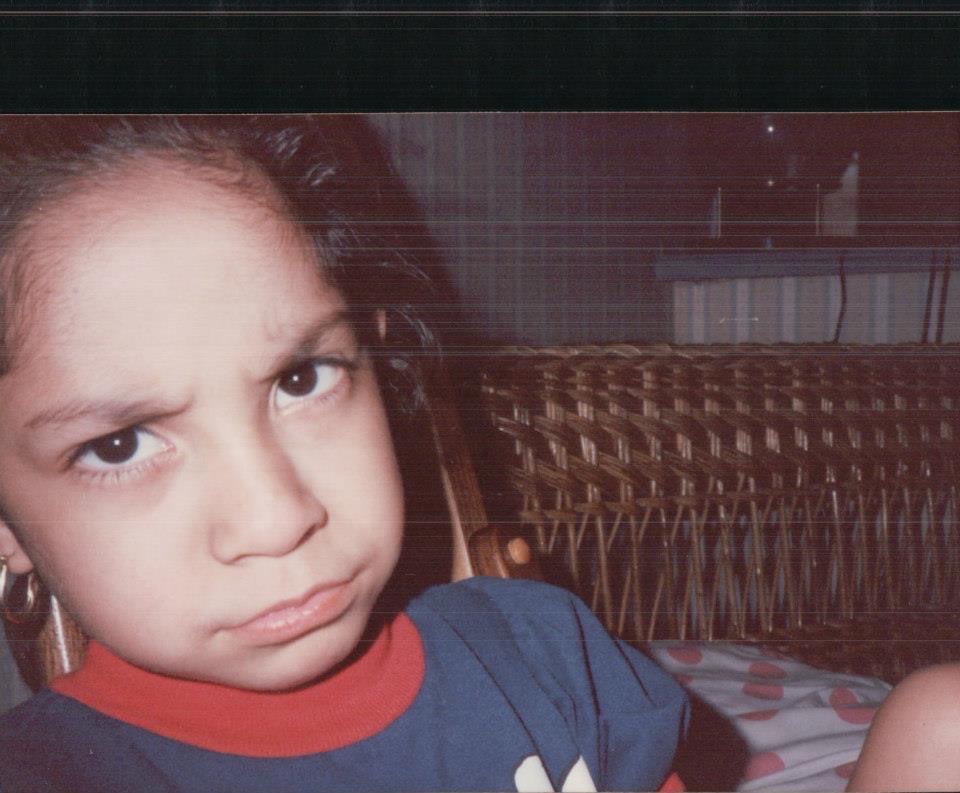

The rupture and wound in Pili’s story also happened during adolescence. After spending her entire childhood in Mexico, at thirteen came the opportunity to go live in the U.S., the country that Pili knew, like many of us, with innocent eyes through Disney shows. In echo with Marco’s story, the preconception that Pili had about the U.S. changed when she started school in Austin, Texas. “I had a very bad time during the first years,” she mentions, “the gringos wouldn’t talk to me, I never fit in. It had been a while since I last practiced English, so I felt really shy about speaking. And when I did I didn’t do it right, so I received a lot of racism from my classmates.” This forced Pili to take a stand: to remain silent or use her voice. She opted for the latter.

It’s young people who are doing this kind of thing and agreeing on a rejection of the colonial… That shift is cool. I don’t know if I’m able to understand it, I just live it and I think it has to do with being receptive to new mexican or latin american music.” – Siete Catorce

Pil found out a way to transform imposition and rejection into an affirmation of identity. Her voice became stronger and critical: after learning English, she began defending those who could not speak English correctly or could not speak English at all: “I spent a lot of time-fighting gringos. I was constantly sent to direction and I would get in all sorts of trouble. I got conduct reports, detention… Basically, I got in trouble for defending my culture.” While I listen to Pil’s sincere and confident voice, I can see how her past left an imprint on the person she is today. Although she prefers working in the shadows and remaining low profile, this is not a synonym for weakness but actually the opposite.

Pil spent several of her teenage years building a library of digital music, but between 2013 and 2014 she discovered bass, footwork and juke. Out of this encounter, a love so profound emerged that these genres not only became the pillars of Pil’s musical production, but also her reason to create the collectives Juke MX and BLDS in collaboration with other artists. As the official statement of Juke Mx reads, its purpose is to “generate and promote a faithful to 160bpm, not only in Mexico but also in Latin America and the world.”

It is worth mentioning that Pil’s moniker, Deeplinkin, encompasses her intention to create community ties through music. After listening to a friend mention the word Deeplinkin, Pil searched for its meaning immediately and knew her name had found her: “I said ‘this is it’. I wanted to connect through these genres that were not known in Mexico. Deeplinkin is the language of connectivity and that’s why I chose this name, to open channels to these genres.” Through the years, Pil has worked to demonstrate that our country also has the wish to explore these sounds and add our own elements. I remember the teenager that Pil described and I connect the dots: it is the same determination and will to use her voice that drives her today, only that now she is focused on the defense of a scene and the love for these genres which were not born in Mexico but came here to stay.

Out of all the perspectives that Pil shares with me, there is another one that stands out for the way it shows her understanding of home: “In the U.S. people are distant and ego-focused, there are no deep connections. In Mexico I’m firewood, unity, family, nature, people. I know that if I’m in the place I grew up in and something happens to me, I will always find help.” Pil approaches electronic music with the same philosophy, she builds ties and believes in a culture of mutual support between labels, clubs and collectives: “One of my concerns is to give something to the scene. I’ve had some plans on how to do it but I understand that I have to go little by little. Now, with the pause caused by the pandemic, what I’m planning may be worth nothing, I don’t know what’s going to happen. Nobody has any answers, but I feel that our homework at this moment is to think about how we are going to click the reset button on the way we were living and build something more positive.”

About to finish our call, Pil asks me if she can add something, and after I say yes, what she reveals is nothing but her most vulnerable side: “To me, being away from Mexico is a state of grief. When you leave your country everything changes, you begin noticing things that you didn’t see when you were there. In the U.S. you’re all good, but over there God knows what’s happening, how bad it’s going to get. I wake up worried about Mexico everyday. What if tomorrow they close borders forever?.” I can sense how Pil’s heart is divided in two, how parts of herself are scattered across different languages and latitudes. However, I also know that Pil is never alone. If there’s one thing she has learned it is that closeness and solidarity are the two balms of pain and doubt. We hang up, and inside me there’s the feeling that I just talked to a very dear friend.

Marco came back to Mexico, Pil went into the U.S., and Lizett, for her part, dwells in the middle ground. In other words, Lizett speaks and creates from the border experience. The way in which she holds on to her identity reminds me of Gloria Anzaldúa when in Borderlands she proclaims “this is my home, this thin edge of barbwire” (3). Born in Laredo, Texas and raised in Mexico, Lizett, like Marco, did not know about her hybrid self until she left Mexico: “It’s an eternal limbo, not being from here but also not being from there. In the Selena movie there’s a quote that has stayed with me through time: Selena’s father tells her that we the TexMex have to be more mexican than the mexican people and more american than the american people. This, of course, is tiring and drains you. In a subconscious way you want to prove that you’re mexican enough or american enough and the truth is you’re neither.”

In addition to the awareness of inhabiting the middle, Lizett lived on the border during Felipe Calderon’s sanguinary, murderous administration: “In 2011 or 2012, I decided to live on the American side because violence increased on the border when the War on Drugs came. This forced many people like me to make a choice. I realized that the life I was living was not normal. I went through it as if it were something from day-to-day life because violence was already normalized,” Lizett recalls. When I mention that I also lived through the ravages of the War on Drugs and that it’s something that still aches in my memory, Lizett knows exactly what I’m talking about: “It’s something that we don’t fully recover from. It marks us all in some way.” Once again (I see it in Lizett’s story) it is clear to me that recognizing this wound inside us and in others is an essential step to establish the point from which we’ll build support networks and change the way we relate to each other.

After leaving Mexico, Lizett was aware of the fact that she was starting her life from scratch. In this blank page is that Rizu X came to be, a project in which Lizett paints the subtleties and experiences of the border through genres such as techno and deep house. Lizett captures the “hot, arid and very dry” climate of her home, she says “all those elements appear one way or another when I’m composing or thinking. It’s a constant image… The river also comes back to me. Especially the river” (Río Bravo is a natural division between the U.S. and the states of Chihuahua, Coahuila and Tamaulipas). Lizett’s work brings me back to the Chicana poets, who retrieved elements of the desert landscape to create a world of images related with the cycle of life and death.

Besides, she adds that “in my approach to producing, I suppose there’s that density, everything I speak on will be marked by the experience of living in between two countries and the War on Drugs. It’s not something easy to put into words, but the way I express it is through music. We may not talk about it directly, but as creative people we are always reflecting it. It’s not necessarily literal, but it gets transmitted somehow.” Gloria Anzaldúa talks about how the people who inhabit the middle, the nepantleros, have to “overcome the tradition of silence” (Borderlands 59) and Lizett fulfills this prophecy in her own way. The violence that permeates the border might condemn us to fearful silence, how is it possible to be anything but stunned after living so close to death? Faced with this landscape, creating in the deserts is a true affirmation of life: “I think that’s what makes me hold on to this place. To me, it’s really valuable to try to create something in the place you’re from. I also want to do something for the border community. It’s about giving the new generations the message that they can also do this, that it’s not only a fantasy. It’s about saying ‘you can also create your own world in this place.’”

Lizett knows that silence cannot be overcome in solitude. When a wound goes through a person and ends up wounding the collective, it is necessary to rethink the way we approach and empathize with those around us. This was one of the first steps that Lizett took upon arriving in the United States: “I started to build a network of artists, of people involved in the same things as I, people with stories like mine who came from McAllen, Reynosa, Matamoros. I was looking to reclaim border identity and realize that we’re not from here but neither from there… I think that we must embrace this identity to know that we’re not alone and that people have been through the same. We can support each other through these communal, artistic efforts.”

Along with two friends, Lizett solidified this desire by creating the La Muy Muy party. Its aim is to join the best of local talent with national one: “My interest was, above all, to build a network. I’m always thinking about ways in which these expressions might reach this place, my home. I want people to know these musical proposals. We knew someone had to do it but we got tired of waiting for someone to take the first step and so far we’ve had really good feedback. I can’t say we’re a big scene at the moment but I know it will come slowly. This takes time and we have to be patient, it’s all about endurance. I’m not expecting anything in return, just continuing until it’s possible and keep on building this network.” Communitary efforts like Lizette’s are as important as individual explorations of the border experience. It’s not possible to share the fruits of these personal inquiries if there are no platforms available. I also believe that the decision to grow artistically in the border is a valuable challenge to the centralization of electronic music in Mexico City. Lizett may agree with me when I say that the border has its own voice and as such it deserves being heard.

Without a doubt, bearing witness to our own wounds brings us closer to the path of mutual recognition and empathy, perhaps the greatest journey we may ever undergo. Today, as we transit a new wound on a global scale (a generalized Nepantla, we could say) it would be necessary to think about the way we are going to understand the word border and how we can work towards building bridges from our position in the world. As people involved in electronic music, we have the opportunity to breathe new life into our bond with this artistic expression and its power to make people come together. I hope the three stories above prove that no bridge is irrelevant or small: we can affect each other’s lives in more ways than we can fathom. It is only fair that I leave the last words of this reflection in the hands of Anzaldúa: “We are all wounded but we can connect through the wound that’s alienated us from others. Let’s put our dismembered psyches and Patrias (homelands) together in new constructions. May we allow spirit to sustain and guide us from the path of dissolution (…) Let us be the healing of the wound.” So be it.

Bibliography

Anzaldúa, Gloria. 1987. Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza. San Francisco:

Aunt Lute.

———. 2005. “Let Us Be the Healing of the Wound: The Coyolxauhqui Imperative — la sombra y el sueño.” In Joysmith and Lomas, 2005.

Interviews/Entrevistas, ed. AnaLouise Keating, 235–50. New York: Routledge.

Mignolo, Walter D., ‘DELINKING’, Cultural Studies, 21:2, 449 – 514.